Lone Traveler Parts 1, 2 and 3The Singular Life of Benjamin Franklin

By Robert A. Crimmins - Parts 1 (1706 (birth) to 1718), 2 (1718 to 1723 Apprenticeship) & 3 (1723 to 1725 Philadelphia)

A portion of Parts 1, 2 & 3 on Benjamin Franklin’s childhood and his first years in Philadelphia

From Chapter 1: Born on Sunday, January 6, 1706 in his father’s house on Milk Street in Boston Benjamin was the youngest son of Josiah Franklin and Josiah’s second wife, Abiah Folger.

It was a loving and nurturing, although strict home. Josiah’s Puritanism was unadulterated. In 1694 he was declared a saint and his devotion was so complete four years later he was elected to the post of tithingman, an official who oversaw one quarter of the families of Boston to ensure their compliance with church-state doctrine and discipline.

Abiah’s father, Peter Folger was an original settler of Nantucket and a resourceful, talented and rebellious man; a surveyor, teacher, writer, miller and clerk of the court who once refused to record court proceedings to protest being granted less land than he felt he was entitled to and during King Phillips War in 1676 he wrote in favor of the Indians and against the Puritan leadership.

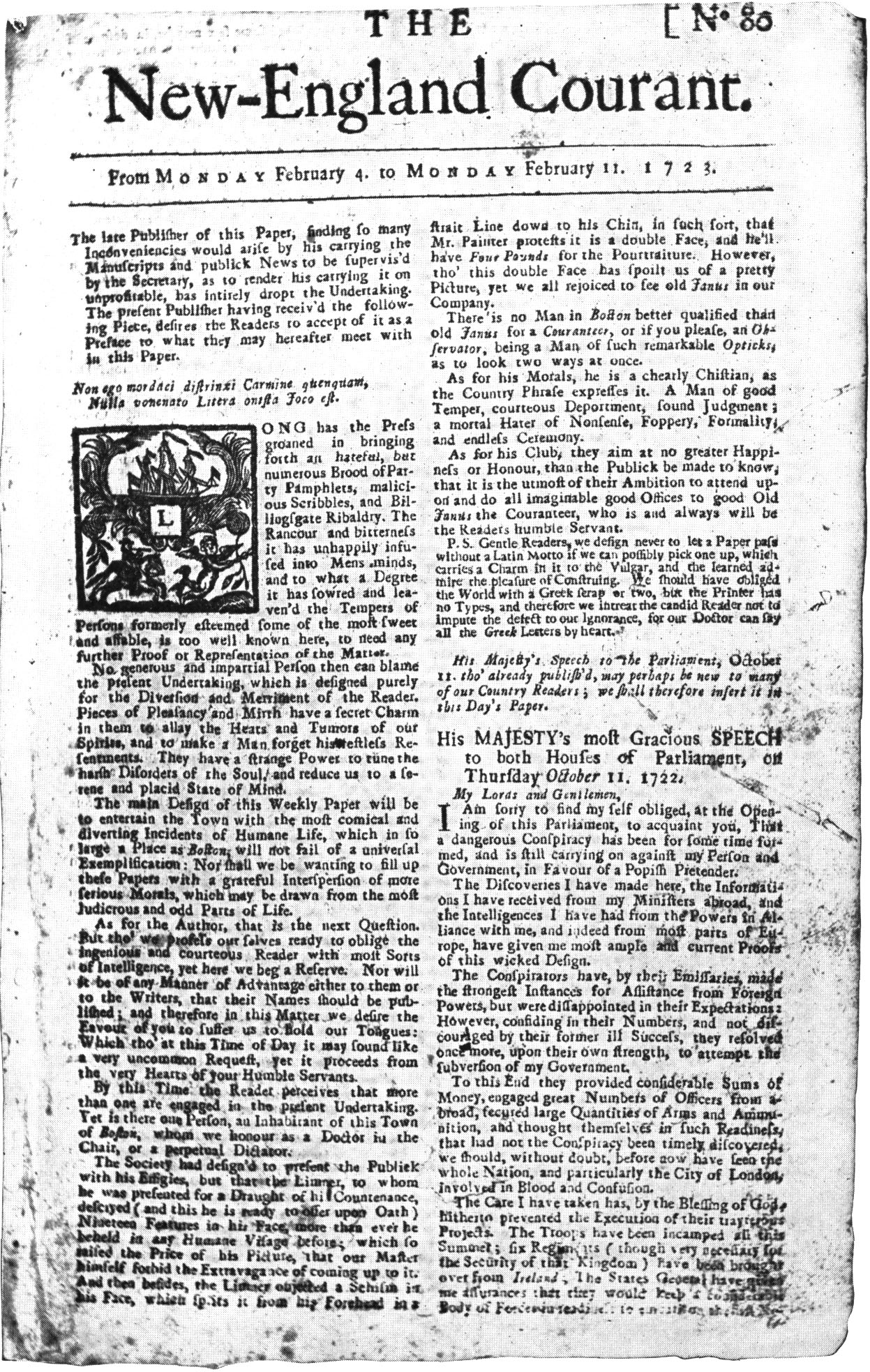

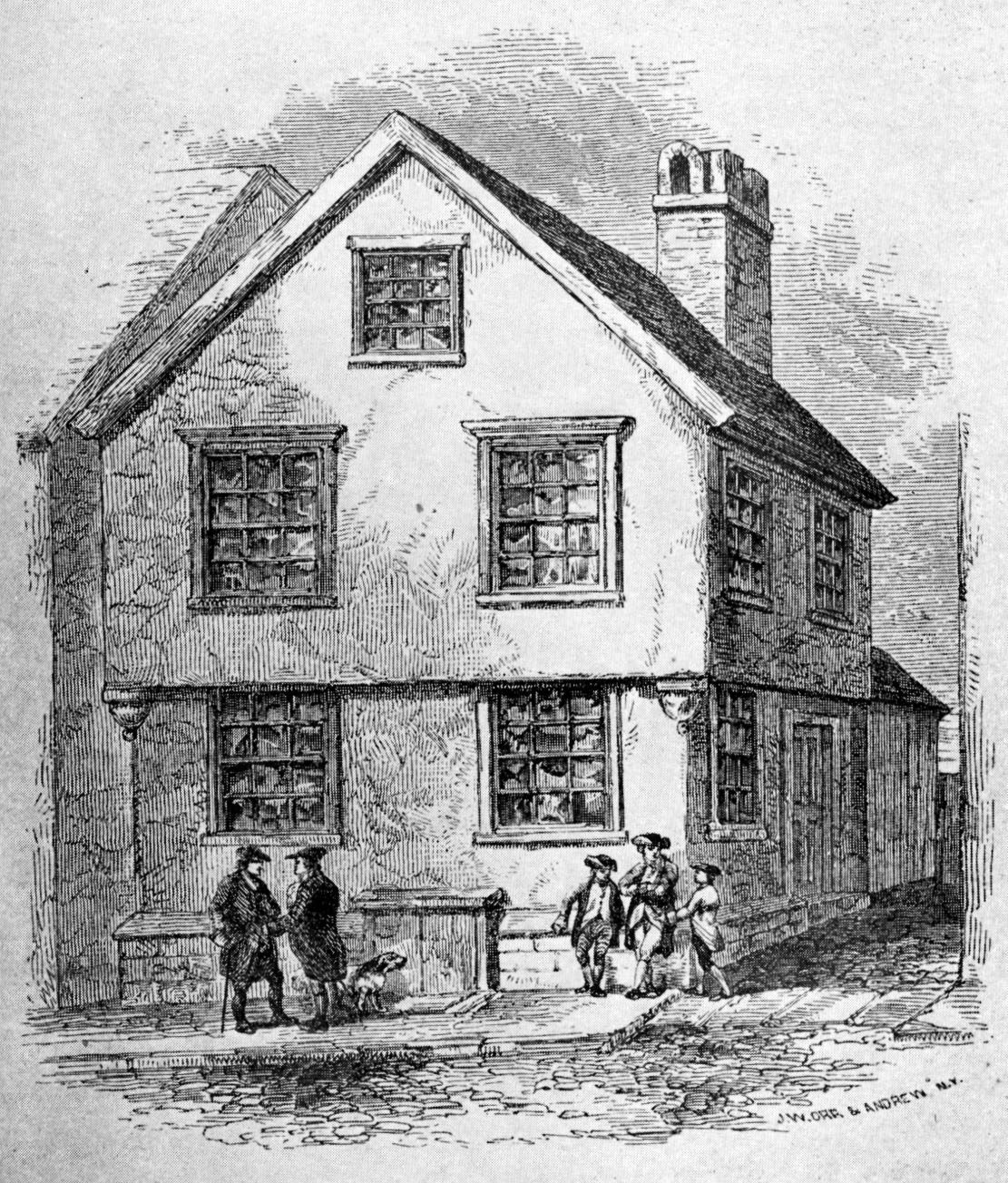

. . . The boy’s love of books persisted so his father settled on the printing trade for his son and placed him in an apprenticeship with Ben’s brother, James. Books were an expensive luxury at the time but as a printer’s assistant the young Franklin had access to books as few others did. Soon Ben was writing poetry and ballads. In his autobiography, which was in the form of a letter to his son William, he wrote:

I now took a fancy to poetry, and made some little pieces; my brother, thinking it might turn to account, encouraged me, and put me on composing occasional ballads. One was called The Lighthouse Tragedy, and contained an account of the drowning of Captain Worthilake, with his two daughters: the other was a sailor’s song, on the taking of Teach (or Blackbeard) the pirate. They were wretched stuff, in the Grub-street-ballad style; and when they were printed he sent me about the town to sell them. The first sold wonderfully, the event being recent, having made a great noise. This flattered my vanity; but my father discouraged me by ridiculing my performances, and telling me verse-makers were generally beggars. So I escaped being a poet, most probably a very bad one; but as prose writing had been of great use to me in the course of my life, and was a principal means of my advancement, I shall tell you how, in such a situation, I acquired what little ability I have in that way.

His ability in that way was striking. Benjamin Franklin became a prolific writer. His success in the telling, and the selling, of the tale of Captain Teach was a powerful lesson. From then on he used the written word to not only build his personal wealth but to influence the course of history. His cleverly conceived editorials and essays written during his tenure in England as the agent for four colonies from 1765 to 1775 and in France while ambassador from 1776 to 1785 were instrumental in the American fight for independence. His pen would become mighty indeed.

From Chapter 3:. . . Ben’s decision to leave his birthplace was daring not only because his prospects outside Boston were unknown but also because he was alone and travel was perilous. In the eighteenth century mankind was composed of thousands of tiny, isolated civilizations. The differences between these diverse societies were great – language, customs, rules of etiquette, the style of wigs and coat tails, all these could change every thirty miles and the variety was a delight to the traveler.

Without police, passports or visas, travel was free, often exciting, and quite dangerous. “Travelers tell fine tales”, was a proverb of the eighteenth century and the traveler was often well received with curiosity and an attentive hospitality, which the old customs still imposed. This was the world into which the seventeen-year-old Franklin thrust himself.

© Robert A. Crimmins, Felton, Delaware, USA

Lone Traveler

CONTACT ROB CRIMMINS

Click on the icon to purchase the Kindle version of the book at Amazon.